LSE is intended as a multi-disciplinary field of work encompassing an understanding of:

The relevant science. This is necessary because the LSE would connect with laboratory personnel and their work environment, understand what they are doing, and translate their needs into working systems. This could be a specialization point for an LSE in electronics, life science applications, physical sciences, etc. However, the basic principles of data acquisition, processing, storage, analysis, etc., are common across sciences, so moving from one scientific discipline to another would not be difficult.

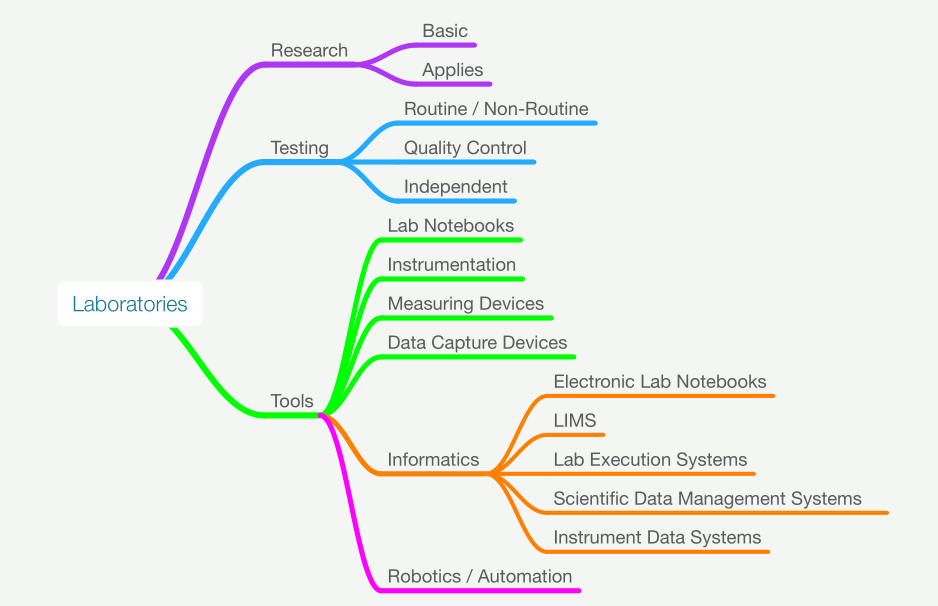

Laboratory Informatics includes LIMS, ELN, SDMS, LES, IDS, digital communications connections (serial, parallel, GPIB, etc.), relevant protocols, analog data acquisition, and related processes etc.

Robotics, including electronics and mechanical engineering principles, and the application of commercial systems to lab work.

Information Systems Technologies, including hardware, operating systems, database applications, and communications. LSEs would not be a replacement for or duplication of traditional IT services. They would bridge the gap between IT services roles and applying those technologies to lab work. In many lab applications, the computer is just one piece of a system that is only fully functional if all the components work together. While this is less of a concern when a system (instruments and computers) is purchased and installed by the vendor, it becomes a significant problem when mixed vendor solutions are being used, for example, the connection of an instrument data system to a LIMS, SDMS, or ELN.

Their skill set should include working with teams and the ability to lead them in the successful development, execution, and completion of projects. This would require interpersonal skills to work with people at various management levels.

Part of the LAE’s role is to examine new technologies and see how they can be applied to lab work. Another is to assess the lab’s needs and anticipate technologies that need to be developed.

An earlier version of this skill set was described under “Laboratory Automation Engineering,” drafted in 2005/2006**. In the almost two decades since that article was released, laboratory informatics and information technologies have become more demanding and sophisticated, requiring a change in the field’s name to reflect those points.

It would also be helpful to have a background in General Systems Theory – This field of work will help LSEs and those they work with describe and understand the interactions between the laboratory informatics systems used in laboratory work. Why is that important in this context? Laboratory Informatics is an interconnected set of components that ideally will operate with minimum human intervention. General Systems Theory* will help describe those components and their interactions.

- “Systems are studied by the general systems theory—an interdisciplinary theory about the nature of complex organizations in nature, society, and science, and is a framework by which one can investigate and/or describe any group of elements that are functioning together to fulfill some objective (whether intended, designed, man-made, or not).”, from: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-381414-2.00004-X.

** “Are You a Laboratory Automation Engineer?”