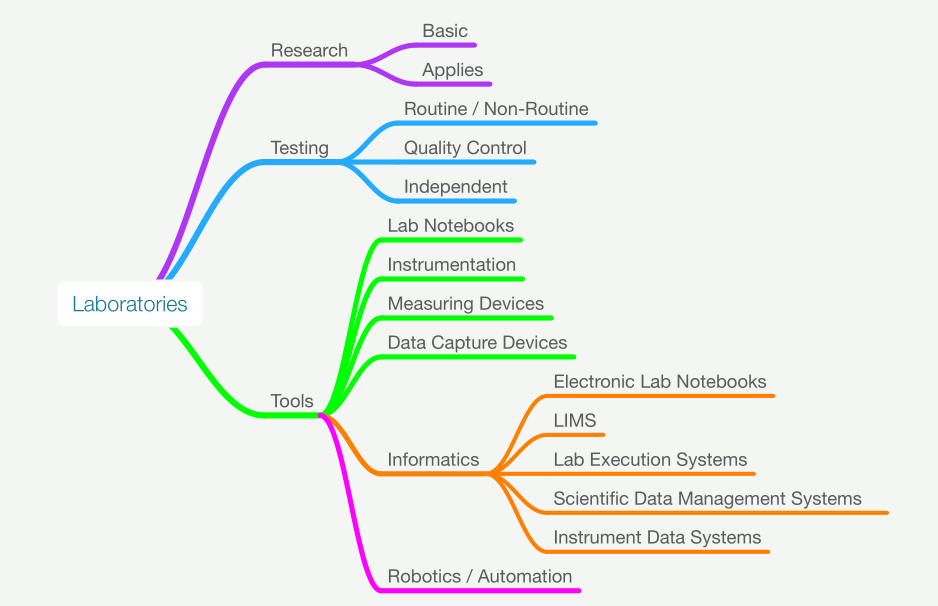

When we enter into discussions about laboratory automation, computing, and informatics, most of the effort is focused on information management (LIMS, LIS, SDMS), data generation (IDS, LES), and robotics (sample manipulation in preparation for data generation). That’s where the products are and where most of the justification for labs and projects originate.

During the course of laboratory experiments, testing, and research, a lot of information, data, and reports are produced that may or may not be well managed. These materials are a valuable product of lab work and when taken together form the organization’s memory. It’s the history of what has been done, why, what the results were including successes and blind alleys. Ever find yourself remembering that someone did some work on a topic that’s now of interest, and wondering where that stuff is?

Developing an organizational memory as part of the lab’s informatics structure, or being extended into a larger organizational matrix, is an important aspect of realizing a return on investment (ROI) in lab work. By taking steps to make that information resource more usable, the ROI can jump significantly by avoiding duplication of work, using people’s time doing manual searches, and coordinating work from multiple sources.

With the advent of artificial intelligence systems, ELN, and LIMS/LIS, we have the basis for developing an organizational memory system. That is what this article is about

To view the material through the LIMSwiki system, click here. (Note: there is no cost for accessing LIMSwiki material. You simply have to login into your account).