This discussion is less about specific technologies than it is about the ability to use advanced laboratory technologies effectively. When we say “effectively,” we mean that those products and technologies should be used successfully to address needs in your lab, and that they improve the lab’s ability to function. If they don’t do that, you’ve wasted your money. Additionally, if the technology in question hasn’t been deployed according to a deliberate plan, your funded projects may not achieve everything they could. Optimally, when applied thoughtfully, the available technologies should result in the transformation of lab work from a labor-intensive effort to one that is intellectually intensive, making the most effective use of people and resources.

People come to the subject of laboratory automation from widely differing perspectives. To some it’s about robotics, to others it’s about laboratory informatics, and even others view it as simply data acquisition and analysis. It all depends on what your interests are, and more importantly what your immediate needs are.

People began working in this field in the 1940s and 1950s, with the work focused on analog electronics to improve instrumentation; this was the first phase of lab automation. Most notably were the development of scanning spectrophotometers and process chromatographs. Those who first encountered this equipment didn’t think much of it and considered it the world as it’s always been. Others who had to deal with products like the Spectronic 20[a] (a single-beam manual spectrophotometer), and use it to develop visible spectra one wavelength measurement at a time, appreciated the automation of scanning instruments.

Mercury switches and timers triggered by cams on a rotating shaft provided chromatographs with the ability to automatically take samples, actuate back flush valves, and take care of other functions without operator intervention. This left the analyst with the task of measuring peaks, developing calibration curves, and performing calculations, at least until data systems became available.

The direction of laboratory automation changed significantly when computer chips became available. In the 1960s, companies such as PerkinElmer were experimenting with the use of computer systems for data acquisition as precursors to commercial products. The availability of general-purpose computers such as the PDP-8 and PDP-12 series (along with the Lab 8e) from Digital Equipment, with other models available from other vendors, made it possible for researchers to connect their instruments to computers and carry out experiments. The development of microprocessors from Intel (4004, 8008) led to the evolution of “intelligent” laboratory equipment ranging from processor-controlled stirring hot-plates to chromatographic integrators.

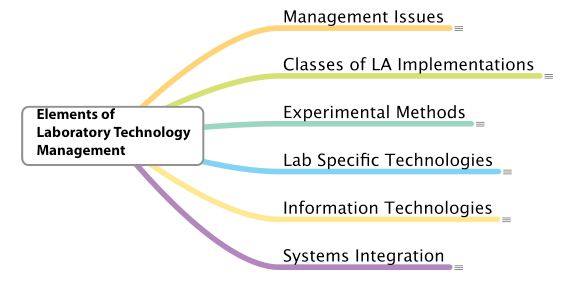

As researchers learned to use these systems, their application rapidly progressed from data acquisition to interactive control of the experiments, including data storage, analysis, and reporting. Today, the product set available for laboratory applications includes data acquisition systems, laboratory information management systems (LIMS), electronic laboratory notebooks (ELNs), laboratory robotics, and specialized components to help researchers, scientists, and technicians apply modern technologies to their work.

While there is a lot of technology available, the question remains “how do you go about using it?” Not only do we need to know how to use it, but we also must do so while avoiding our own biases about how computer systems operate. Our familiarity with using computer systems in our daily lives may cause us to assume they are doing what we need them to do, without questioning how it actually gets done. “The vendor knows what they are doing” is a poor reason for not testing and evaluating control parameters to ensure they are suitable and appropriate for your work.

View the full article on LIMSforum